Baker's Dozen - Standouts in Fighting Game Execution Design

NO AI TRAINING: Without in any way limiting the author’s [and publisher’s] exclusive rights under copyright, any use of this publication to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

“Fighting games are hard.”

This sentiment has been echoed for as long as the genre has been around. Riot’s new fighting game 2XKO has sparked a revival in the discussion on accessibility within the genre. With the design team’s emphasis on encouraging players new to fighting games to give it a go, concessions have been made with respect to the controls in order to have the game be as accessible as possible to an uninitiated audience. As far as how successful they’ve been in this regard remains to be seen; it’s far too early to tell.

With the end of the 2XKO Alpha Lab upon us, I thought I would take this time to publish an article that I had written for a friend working in game design. As they were inexperienced in the world of fighting games, they wanted a primer on the genre addressing the whole entry-barrier spectrum.

Here are 13 games I think are standout examples of execution design philosophy across the fighting game landscape:

Couldn't Be Simpler

Divekick

Divekick is a game beloved by fighting game fans that involves two buttons and no directional input. One button makes you jump and the other does your divekick. That's literally it. One hit to KO and a few rounds to win. It's insanely fun and literally anyone can play it. All the nuance is in your button timings and knowledge of the characters’ trajectories.

Tourney footage:

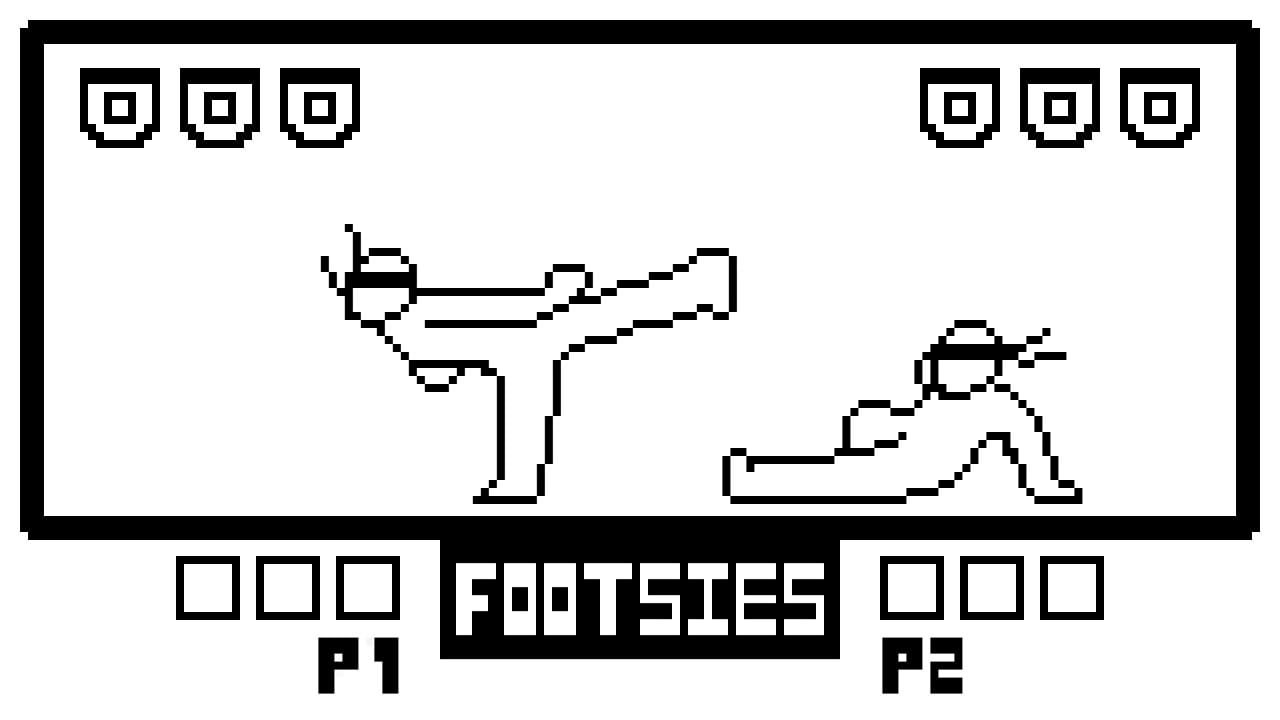

Footsies

Developed by HiFight, an FGC content creator, this extremely simple fighting game boils down the essence of fighting games and distills it. The term “footsies” is an FGCism referring to the utilization of movement and attacks to hit the opponent when they’re unprepared or to force the opponent to whiff and punish their recovery frames.

Footsies is one layer more complicated than Divekick as it trades the jump button for binary forwards/backwards movement. The attack button pressed while not moving executes a crouching kick that can then be “hit-confirmed,” meaning that if you react to it hitting the opponent while they’re not blocking you can then cancel the move into another attack and win the round. A direction with attack executes another cancellable move: a knee that is slightly faster than the neutral attack, though shorter in range. Holding the button and releasing it executes an extremely unsafe sidekick special move that upon hitting an opponent that isn’t blocking will immediately net the player the round, though it being blocked will lead to it being punished by the opponent. When held down with a direction, the attack button will on release execute an invincible uppercut that carries similar risk/reward as the sidekick.

The combination of extremely easy execution, simple presentation and implementation of a rollback netcode before most major fighting game developers did has led to Footsies being an absolute smash in the FGC, historically being an extremely popular side game. This game gets fighting games.

Tourney footage:

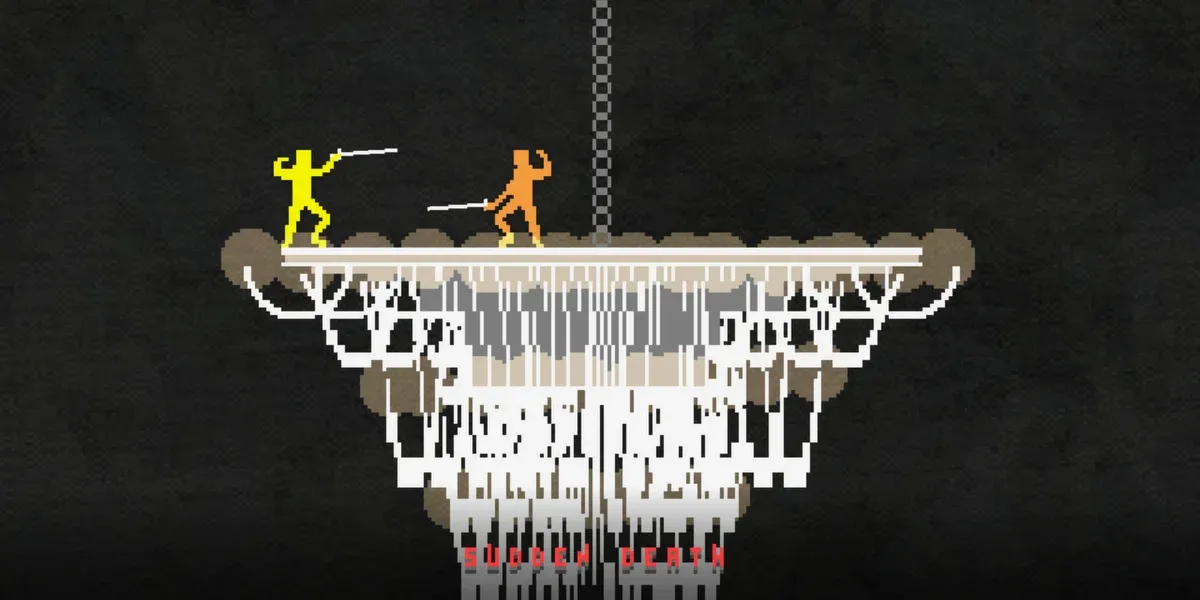

Nidhogg

Nidhogg is a fencing game where both players are attempting to get to the other side of a linear level while attempting to impede each other's progress. Another two button game (jump and action), directional holds and timed button presses gives each player access to additional moves such as lunging, throwing, dive-kicking, tripping and more. Nidhogg is an excellent example of doing a lot with very little. There is a sequel as well though I cannot speak for it.

Tourney footage:

Extremely Simple

Fantasy Strike

Developed by David Sirlin (fighting game player and game dev) this game eschews traditional controls in order to ease entry for players. Controls are:

-Left/Right

-Jump

-Attack

-Special 1

-Special 2

-Super

-Throw

The game also simplifies damage into sectioned health bars so the gamestate is always extremely transparent.

Fantasy Strike never picked up too much steam in the community, partially due to being graphically, well, ugly. The game is based on Sirlin's fighting/card game "Yomi," which is extremely unique in its own way of distilling fighting games and I would suggest giving it a look just for its design.

Tourney footage:

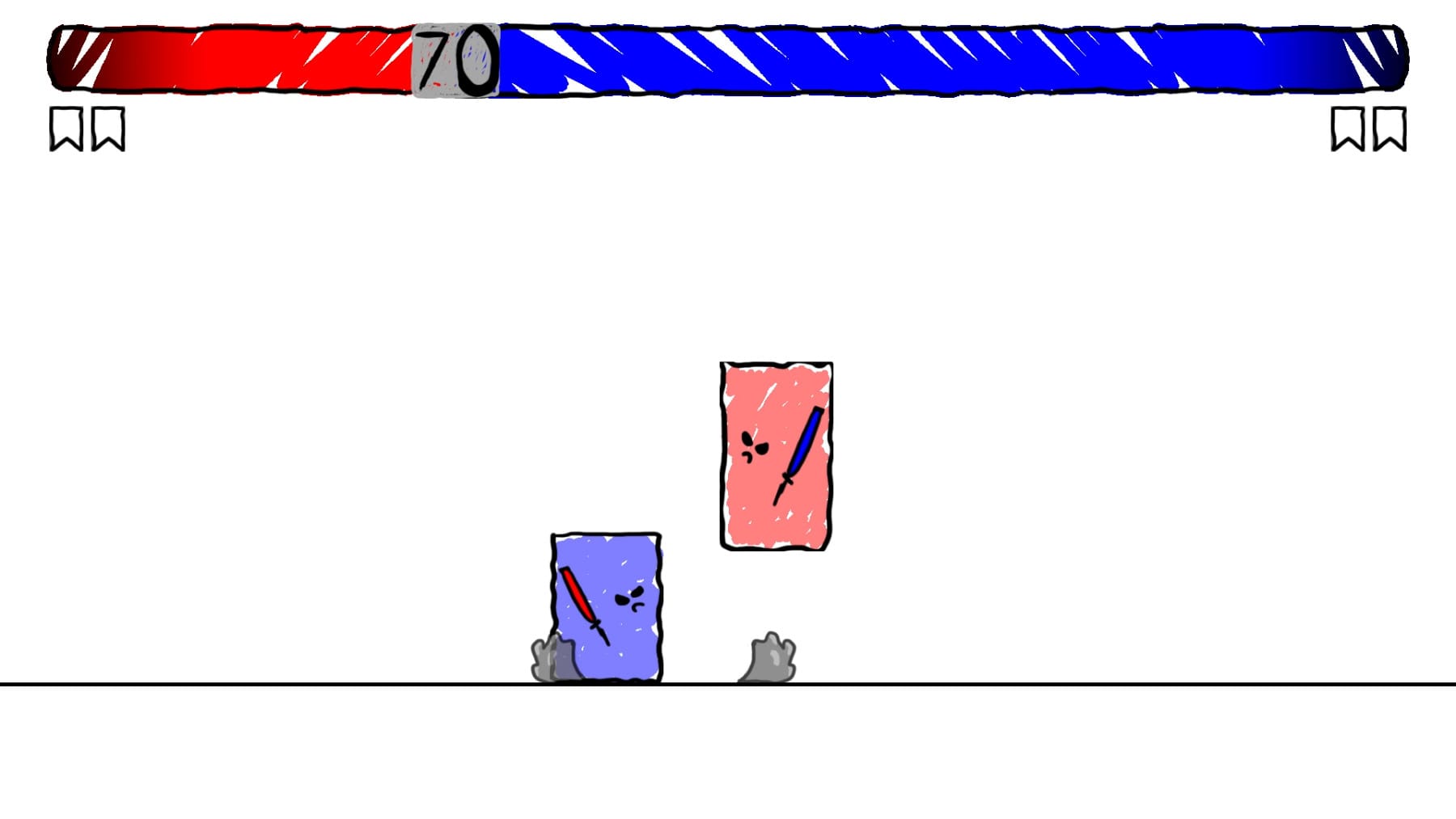

NAIR/DAIR

These are platform fighters that reference Neutral air and Down air, colloquial terms for aerial attacks in the Smash franchise. Both games utilize simplified controls: analog movement, a jump button, an air dodge button and an attack button that is only actionable when your character is in an aerial state. Both games allow for advanced movement options utilizing the stage (such as walljumps) or directional air dodging, the latter notably giving the player the option to wavedash/waveland for more expressive movement.

Also to note is the health system, which is unique in that it is akin to tug-of-war. A player has to get a certain number of hits more than their opponent to win a round. DAIR is different in that additionally if a player spikes their opponent into the blast zone they immediately win the game.

There is no real scene for these games that I know of, likely due to being small indie games with no IP attached to them unlike Smash, Nickelodeon All-Stars Brawl or Multiverses. NAIR/DAIR will likely stay extremely niche, which I think is a shame. I ran a mystery game tournament recently and both of these titles were extremely well-received by all that played them, fighting game players or not.

Easy to Pick Up, Hard to Master

Mobile Suit Gundam Extreme VS Series

The Gundam VS series has single-handedly carried the revenue of arcades and game centers in Japan for years. It is no exaggeration to say that this franchise is responsible for these arcades not having shut down yet. Entire floors of arcades are dedicated to only cabinets of this series.

This game, like 2XKO, is a 2v2 fighting game. However, unlike 2XKO this differs in two major ways.

1 - All four players are on the field at the same time, save for respawn timers.

2 - This is a 3-D Arena fighter, a genre that is often scoffed upon by the greater FGC. This game, however, is an exception. EXVS could easily be another anime tie-in game cash grab, but the developers made this game specifically with its core audience in mind: the competitive scene. This is a game crafted specifically to be played competitively and in arcades.

Teams must share a resource which is referred to as “cost.” Each unit in the game has a different amount of cost assigned to them. Each unit has their own individual health, and when the health runs out that unit's cost is deducted from the team's total cost pool. The object of the game is to deplete your opponents’ cost by landing hits and destroying the opponents’ units.

On a 3-D plane, situational awareness is an absolute must. The player must not only be acutely aware of their positioning, but also their teammate’s positioning, their opponents’ positioning, as well as all players’ positioning relative to the 3D plane.

The control scheme is very simple: directional movement, a shoot button, a melee button, a boost button, and a button to switch between enemy targets. Despite this simplicity, the game is extremely mechanically deep. From an execution perspective, different combinations of buttons along with different cardinal directions that they’re pressed with results in different moves. Certain moves chain into others. Certain moves can be canceled into other attacks, installs or movement options.

Movement is controlled by the utilization of the movement stick and the boost button. Advanced actions in the game cost boost gauge. Different options lead to different levels of boost being spent. This gauge refills only if you are not moving at all. One must carefully weigh how much meter they spend versus the position that they put themselves into. For example, one could go gangbusters and spend absolutely everything in pursuit of an opponent, but then they will have to stand still for a longer period of time in which their opponent’s partner could potentially hit them with a devastating punish.

Strategy in the EXVS series is dense, with players having to constantly juggle cost, boost and ammo management, acute 3-D spatial awareness and complex team coordination. The depth of this game along with the attachment of a popular IP in Gundam has led to this game’s extreme (ha) popularity overseas.

Tourney footage:

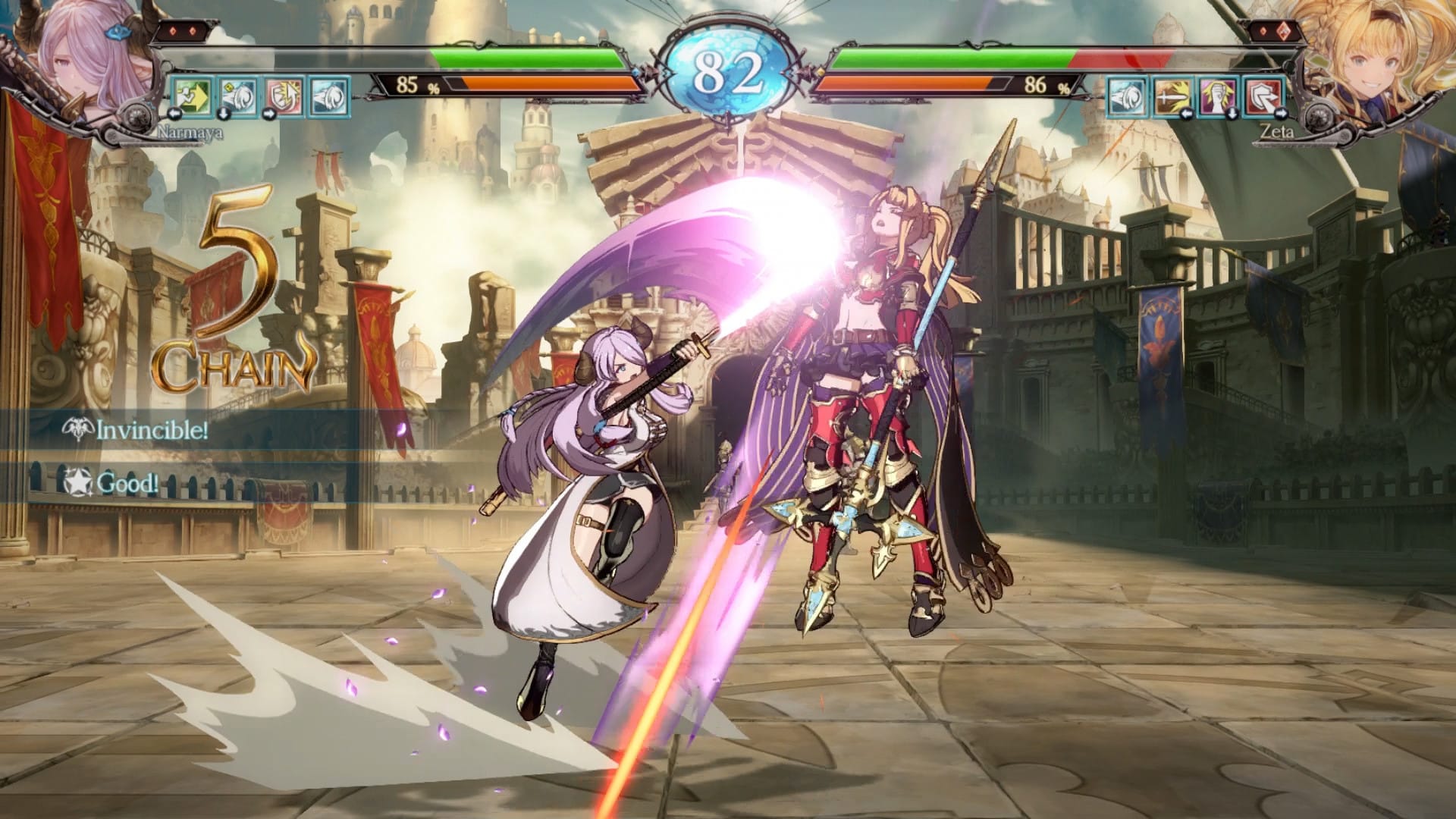

Granblue Fantasy Versus

GBVS is a traditional 2-D fighting game that broke the mold in its first installment by introducing a few ease-of-use accessibility options for its players. The game was crafted and balanced specifically around the availability of these options.

One way that the game differs from other fighting games is the utilization of a block button. This is also used in the Mortal Kombat series, however, this is an approach that has not been popularly used.

Another way that the game differs from its peers is the utilization of a special button. Both specials, as well as supers, can be executed quickly by simply pressing a button with a direction, much like Smash. This does not replace the traditional input method for special moves such as a quarter-circle or DP input, but exists as an additional way of executing them. An option’s strength is often weighed against its ease-of-use, so players were extremely skeptical of giving the ability to do, say, one button anti-airs to everyone and their grandmother. As such, the devs instituted a cooldown system similar a MOBA or Diablo. Every special move has an associated cooldown; using the special button will result in a longer cooldown for that option than using the traditional input. This tempered a lot of players’ anxieties regarding the balance of the game at the cost of the initial execution entry-barrier.

This design philosophy changed in the sequel, Granblue Fantasy Versus: Rising, but vanilla GBVS is widely accepted as a rousing success for both casual as well as hardcore players, netcode notwithstanding.

Tourney footage:

Street Fighter 6

As the franchise that invented the genre, a lot was expected of the newest installment of the Street Fighter series, Street Fighter 6. Much like the aforementioned GBVS the game has opted to also institute an accessible, so-called “Modern” control scheme. This is not forced upon the player. In fact, one can choose between multiple different control options at the character select screen. Like in GBVS, the control scheme allows for one button specials. It also allows one to do auto combos by holding down an assist button and mashing an attack button. Modern has a few drawbacks: reduced damage using the special button, as well as a limited three-button normal attack pool as opposed to six, resulting in limited accessibility to their character’s moveset. That being said, most competitive players still play with “Classic” controls, though there are a few exceptions at all levels of the game.

Another way SF6 differs from its predecessors is the “Drive” system. Drive meter is gained by taking aggressive actions or naturally refilling over time. Drive meter is taken away from the player by spending it, blocking the opponent’s attacks, or being hit by certain moves. This meter can be spent for access to more powerful versions of characters’ moves, advanced movement options, canceling moves for combo or pressure purposes, and much more. If a character runs out of drive, they are considered “burnt out,” and take a number of penalties including the opponent’s moves all being more advantageous on block, taking chip damage, and being open to an unblockable drive move called “drive impact.” At round start both players begin with full drive meter. In addition to playing footsies and anti-airing, the bulk of decision points in this SF iteration consist of careful meter-management. Deciding when to spend or save meter, when to prioritize health or meter damage, as well as countless other considerations made on the fly results in extremely robust strategic depth. Even with simple execution in Modern, this does not cheapen the complex decision-making that all players must go through.

With the inclusion of this new control scheme, as well as an extensive single player open-world RPG game mode, has led to SF6 being embraced and celebrated among casual and competitive players alike. It, along with Tekken 8, are the two leaders in the FGC in terms of popularity.

Tourney footage:

“Crunchy” Games

Capcom vs. SNK 2

CvS2 was a collaborative effort between major fighting game developers Capcom and SNK. This is a 3v3 team game that has two distinct differences from its contemporaries.

First is the ratio system. A player selects between one and three characters and divides among them up to four “ratio.” The higher a character’s ratio value, the more health and more damage that character has.

Its second distinction is that the system mechanics are divided into six “Grooves.” At character select, one chooses which Groove they’d like their team to use. The Groove allows characters to have the system mechanics of different games from Capcom and SNK titles. For example one Groove could give dashes to your team or allow them to run. One could introduce shorthopping, or another allows you to block in the air. Some allow you to parry, while others may give access to rolls or guard-cancels. The Grooves also change the types of super moves that your characters have. One could allow you to only use one big super, or choose between several smaller ones. One Groove, in particular, allows characters to literally combo any move into each other. Due to the combination of 48 characters and six different Grooves, there are innumerable team combinations that players can tinker with.

CvS2 is from 2001, and older fighting games are far less lenient than their modern progeny in terms of execution. With no input buffer, lever motions must be incredibly clean and button timings very often must be literally frame perfect. Add all these factors together and this makes CvS2 a game that keeps providing players with continued growth after over 20 years of competition.

Tourney footage:

Super Smash Bros. Melee

Melee and CvS2 were both released in 2001. Though both titles have seen regular competitive play, Melee’s playerbase has remained extremely consistent throughout the years. In fact, Melee may be more popular now than it ever has been. Melee was not designed specifically with tournament play in mind, but many quirks of its physics system has led to an enthusiastic competitive scene being born from it.

In most fighting games, being comboed is an uninteractive process; “I hit this move and that leads to this move,” etc. Two examples from fighting games that are exceptions are the “combo breaker” system in Killer Instinct, and “bursts” from the Guilty Gear series. Melee takes a different approach with “Directional Influence,” or “DI”, for short. When a player is being comboed, they can alter their trajectory by holding a direction. This means the comboer must read or react to these adjustments mid-combo. The offense can also net early kills by setting “DI traps,” reading the opponent’s DI and placing them into a worse position had they used a different angle. This constant interactivity means there is no mental downtime, whether on offense or defense.

Another trademark that separates Melee from the rest of the pack is the incredible depth of movement that the game has to offer. This lends the game to having a kineticism unmatched by any other. Walking, running, dashdancing, shorthopping, turning, wavedashing, foxtrotting, moonwalking, pivoting, boosting, ledgecanceling, momentum cancelling, b- reversing…the list seemingly never ends.

Like CVS2, Melee also has no input buffer. This means that whatever you do is going to be accurately reflected within the game, unlike successive titles like Ultimate, notorious for its enormous buffer window. The combination of these two factors allows the player, I’d argue more than any other game in history, to have complete control and expression with their character. If you ask almost any player what their favorite part of Melee is, they will more than likely answer, “It just feels good.” It takes a lot of work in order to be able to pilot one’s character in such a way that they achieve this, meaning that the skill floor is extremely high compared to almost any other fighter. That being said, the room for growth and improvement in the game is basically endless, with over 20 year competitive veterans in the scene regularly changing their playstyles, inventing new techniques and honing existing ones.

Melee, with its extensive history, likely has the most developed meta-game of any competitive video game. There has been a competitive scene for this game for almost a quarter of a century. This has been almost entirely a grassroots effort. Rather than provide support, Nintendo has even actively tried to tear down this scene with C+Ds and threatened lawsuits. But the community has often likened itself to cockroaches; you just can’t kill them. Their love for the game rivals that of any other scene, and I’d like to think that the main reason is not just the familiar IP that it is attached to, but more so for the technical prowess that can develop, and ultimately the amount of control that one can feel upon achieving mastery over their character.

Tourney footage;

Ultimate Marvel Vs Capcom 3

UMVC3 is a 3v3 tag-team fighting game. In any tag-team game there is a character that the player is controlling, as well as the ability to use assist moves from their back characters. When these characters use their assist moves they are as vulnerable as any other character on the screen so one must be judicious about when to use them. There are several ways in which you can tag in or out your team, some of which are safer than others. When a character is on the bench, there is a certain percentage of missing health that they passively regenerate over time, so sometimes it is prudent to pull your character to let them get a little healthier.

In most 3v3 tag games there is a “point” character who is sent out first but requires assists to make them perform well, a “mid” character who generally has a strong assist move, and an anchor which acts as a means to close out games or mount a comeback. With 50 characters, the number of different team combinations becomes staggering.

There are three major things to understand about Marvel, and tag team fighters in general.

First, it’s that offense is incredibly strong. The pressure and mixups that one can apply to a defending player utilizing three characters at once is absolutely insane. Understanding what is going on when the screen more resembles a bullet-hell game than a fighting game is incredibly difficult.

Second, it's an extremely high-damage game. One wrong defensive read, or worse, minor execution error and it’s likely the last time you’ll see your character alive on the screen.

Lastly, Marvel is an incredibly hard execution game, both in terms of skill floor as well as ceiling. Combos are extremely freeform and keeping all the rules straight for differing character weights, combo points, resource management etc. are extremely difficult to keep straight. Execution itself is incredibly difficult, with many advanced movements and Option Selects available to the player.

This game is hard.

Tourney footage:

Expanding the Definition

Lastly I’d like to introduce two games made by local devs that were born out of a love for the genre. Though not traditionally “fighting games,” they carry the same DNA and both have a low barrier of entry.

Eucloid

Eucloid is a 1v1 top-down versus game where players attempt to hit the opponent and avoid being hit themselves. Matches take place in a square arena, in the center of which spawn shards that build meter for the player. There are four different characters for players to choose from: Tether, Turtle, Daemon and Gemini. Each of these wildly different characters are piloted using a controller’s dual analog sticks. Rounds are single-hit wins, leading to extremely fast and frenetic gameplay. The developer, bitq, made the game as a gateway into traditional fighters. With no combos, frame data or complicated motion inputs, Eucloid introduces players to spacing, meter management, yomi and other FGCisms without the necessity of hours spent in the training room.

Tourney footage:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EUbdnkcfQTY

A Sound Plan

A Sound Plan is another top-down 2D arena fighter designed by local developer Dean Hulse. Players chuck rocks at each other to do damage and stun their opponents. Rocks are a finite resource, though players can dig for more at risk of leaving themselves temporarily vulnerable. Zombies also populate the arena and will instantly kill a player that they get their hands on. Like the punny title implies, sound is a key element in the game. Players can attract zombies by throwing rocks at objects near them in an attempt to draw them towards their opponents. What results is an immediately accessible competitive game that can be both either highly tactical or absolute mayhem.

https://www.youtube.com/@deanhulse4450

Eucloid and A Sound Plan were both regularly run as side brackets at local fighting game tournaments, much to the delight of the community. They are extremely simple and not what you'd visualize when you think "fighting games," devoid of the usual kicks, punches and fireballs. But fighting games aren’t about long combos or complicated inputs: they’re about interactivity between competitors. A niche genre can often be an echo-chamber, never growing their core audience. A reduced barrier of entry means less initial obstacles between execution and appreciation for what fighting games have to offer. This is not a replacement for our hardcore scene. If we remain tied down to aesthetics and traditions then perhaps we, too, will miss out on growing our beloved genre.